Five years of a collective effort to sustainably harvest, propagate, and grow seeds from native plants is bearing fruit.

Development, mining, overgrazing, climate-change-related extreme weather, and the spread of invasive species have led to rapid declines in native plant populations across the United States, reports the U.S. Bureau of Land Management. Throughout the Northeast, hundreds of native plants are under threat. As more people learn about the importance of native host plants to native pollinators and other wildlife, demand has flourished and outpaced supply.

Yet most plants sold as “natives” are not grown from local seeds from the ecoregion – a land or water area with distinctive climate, ecological features, and plant and animal communities – in which they’re being sold. Many come from the Midwest, says Geordie Elkins, executive director of Highstead. A 2018 survey of East Coast native plant and seed users found they source their plants an average of 418 miles away, reports the Mid-Atlantic Regional Seed Bank and the University of Maryland Extension. “Ecotypes are the heirlooms of our pollinators; they are the truly local, source-identified, and provenanced seeds that are, genetically speaking, the most appropriate for our landscapes, and therefore have the greatest chance of persistence,” says Sefra Alexandra, co-founder of The Ecotype Project, a program to bolster the local native plant supply. Growing the same species from a different ecoregion can be problematic: If, say, a milkweed sourced from Tennessee exhibits a different bloom time than a local variety, this may cause monarch butterflies to stick around and delay their migration trip south, missing the blooming of their host plants as they travel down the coast, she says.

After five years, The Ecotype Project’s strategy to mentor small farmers in ecotypic seed production has spread across Connecticut and the Northeast. It now spans five states – Connecticut, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, and Rhode Island. The Ecotype Project, started as an initiative of the Northeast Organic Farming Association of Connecticut (CT NOFA), has been the leading force in training a new cohort of seed farmers in the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s classification known as Ecoregion 59 to increase native seeds’ availability. This ecoregion includes most of Connecticut, Rhode Island, and parts of Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and southern Maine.

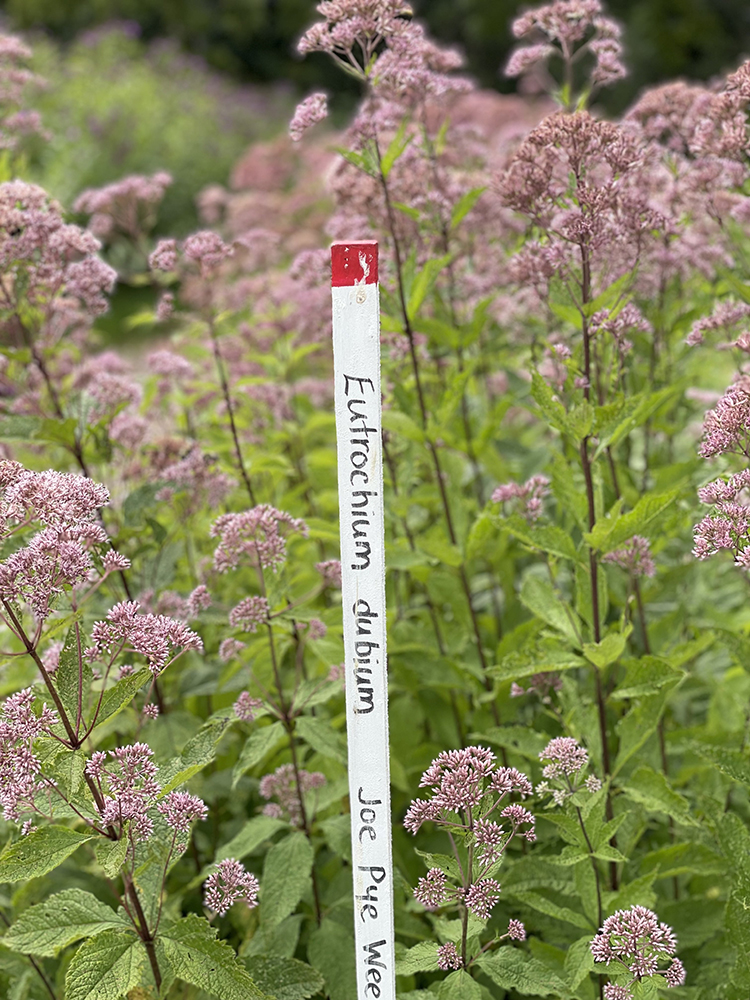

Fifteen farmers are growing 50 different native species in this seed-production pipeline. These seeds are sold through the farmer-led Northeast Seed Collective, and plugs are now available at partner wholesale and retail nurseries so homeowners, conservation groups, and others trying to plant for pollinators can buy these local pollinator plants. Farmers interested in getting involved should contact the Northeast Seed Collective, which sells ecotypic seeds through its website.

Local Seed Sourcing

Locally sourced native seeds and plants are scarce and outstripped by ever-increasing demand. But the region’s conservation lands, such as Highstead, host vibrant native plant populations. Highstead and regional partners are part of a national and global effort to sustainably collect, propagate, and increase the amount of ecotypic restoration seed for local land use needs, Alexandra says. The U.S. Bureau of Land Management established a National Seed Strategy for Rehabilitation and Restoration, to provide the USA with a template to build regional seed networks.

The Bureau of Land Management, the largest federal land manager in the U.S., oversees about one-tenth of the country’s land, mostly in the West and Midwest, but very little in the Northeast, Elkins says. So, it fell to private conservation nonprofit organizations to take the lead.

Highstead is part of this farmer-led seed collective, a regional movement to harvest and grow native plant seeds that are just right for the wildlife that depends on them. Scientists, conservationists, home gardeners, and farmers are collaborating to increase the number of region-specific, ecotype plants that have co-evolved with and support the region’s pollinators.

Highstead is one of several conservation sites participating in the effort, and staff harvests native seeds from its conservation lands and helps to clean, stratify, and grow starter plugs that can then be shared with farmers to grow large enough for sale. Elkins and the Highstead team advised on protocols for how and when to harvest seeds without negatively impacting the wild populations, including the steps of collecting, germ testing, drying, cleaning, storing, and propagation.

“Seed is this vital natural resource. We want to make sure seed collectors have permission and are trained in best practices such as knowing to harvest a certain percentage of a wild population to safeguard these vital natural resources in our fragmented landscapes,” Alexandra says.

“The Ecotype Project created a model to increase the ecotypic seed supply of genetically appropriate plant material vital to the ecological restoration of the Northeast. Farmers know how to grow plants; our project has mentored this cohort to understand the benefits of producing this specialty seed crop on their land,” she says. Increasing native plant diversity on farms increases the presence of beneficial insects and decreases the presence of pests, she says, which is an organic approach to pest management.

“Pollinators are ensuring the future viability of our foodshed and agrarian livelihoods,” adds Dina Brewster, former executive director of CT NOFA and The Ecotype Project co-founder. One major challenge ecotypic seed advocates face is getting the quantity of quality native seeds needed, says Brewster, owner of The Hickories farm in Ridgefield, Connecticut, and fellow Northeast Seed Network steering committee member with Elkins and Alexandra.

Spreading to Land Trusts

Some land trust staff and volunteers are being trained in how to sustainably harvest seeds from their properties so they can be grown for later planting on the land trusts’ property to combat invasive plants, says Mary Ellen Lemay, director of landowner engagement for the Aspetuck Land Trust in Westport, Connecticut. Land trusts are propagating trees, shrubs, and perennials, she says. Elkins and Brewster collected white oak acorns from Aspetuck’s property, and they are growing seedlings.

“This is kind of a new direction for land trusts to really think about themselves as being the keeper of the seeds,” Lemay says. “The preserved land is the most resilient. It has species you sometimes don’t find in other places.” In a few years, once the seedlings have grown, land trust staff and volunteers plan to plant them in urban forests in nearby Bridgeport.

In addition to the trees, Highstead staff is propagating grasses, milkweed, and several additional perennials that land trust volunteers plan to plant on Aspetuck preserves. While they’re growing, Aspetuck’s land stewardship director is leading teams of volunteers to remove invasives from along Aspetuck’s trails, she says. In the past few years, the Aspetuck Land Trust has bought ecotype plants from Planter’s Choice wholesale nursery, and volunteer crews have planted them into an area where they had removed invasives.

One of the greatest tools of resilience in the ecological restorationist’s toolbox is using genetically appropriate, ecotypic plant material for reseeding the living seed bank, the soil, with plants that will survive and thrive, Alexandra says. The motto of the national native seed movement is, “Put the right plants in the right place at the right time.”

Consumers can help encourage nurseries to sell native ecotypes by asking, “Do you have any plants grown from locally provenanced seed?” Alexandra suggests. “Together we can help to fortify seed sheds by promoting plant material from a seed collected, grown, and sold in your local ecoregion.”