Dicken Crane was destined to become a conservationist. “I was born into it,” he says. “My great-grandfather’s grandfather came to Dalton to build a paper mill. The original incentive to acquire land was to protect the watershed that provided hydropower to run the mills. My great-grandfather and other family members were interested in the agricultural, forestry, and wildlife benefits that came from protecting the watershed, and that tradition continues four generations later.”

Today Crane owns and manages a thousand acres of forestland and 200 acres of farmland, including Holiday Brook Farm, a diversified farm in Dalton, Massachusetts. He also serves as board chair of the Woodlands Partnership of Northwest Massachusetts, a Regional Conservation Partnership (RCP) encompassing 21 towns in the northwest corner of the state.

“Northwest Massachusetts is a very forested region, and it’s identified as a priority in both the State Forest Action Plan and federally recognized as an important area,” says Lisa Hayden, administrative agent for the Partnership, which began in 2013 as an advisory committee focused on forest conservation. At the time, the U.S. Forest Service was considering expanding Vermont’s Green Mountain National Forest into the Commonwealth.

“The region has many towns with more than 50% state-owned land, so it didn’t seem like a good idea to add more state land,” says Crane. “And there was a lot of concern over the viability of the small towns and a decline in the rural, natural resource-based economies. The sustainability was in jeopardy.”

In 2018, the organization became a legal entity under the name “Mohawk Trail Woodlands Partnership.” The New England Forestry Foundation currently serves as both a fiscal sponsor and administrator overseeing daily operations in support of the 30-member board, which includes representatives from municipalities, land trusts, regional planning agencies, economic development groups, UMass, and other organizations.

“When you attend our board meetings, it’s a group of local people who are very familiar with the towns; the job opportunities; the challenges, particularly in rural towns, to provide services—schools, fire services, ambulance services. Those are things that the local community understands in a way that some outside group just wouldn’t know. That’s the benefit of having a board made up of local people who intrinsically understand what’s going on,” says Crane.

In 2022, the board voted unanimously to change its name to the Woodlands Partnership of Northwest Massachusetts in response to concerns that the former name was both inaccurate (the Mohawk historically lived in what is now New York state) and “contributing to making local Indigenous folks seem more invisible.” They also expanded board membership to include Indigenous representation from the Ohketeau Cultural Center, a Nipmuc-centered, multi-tribal organization based in Ashfield. Rhonda Anderson, a Native Alaskan who grew up in northwest Massachusetts and currently serves as Western Massachusetts Commissioner on Indian Affairs, is the first Indigenous representative on the Partnership board.

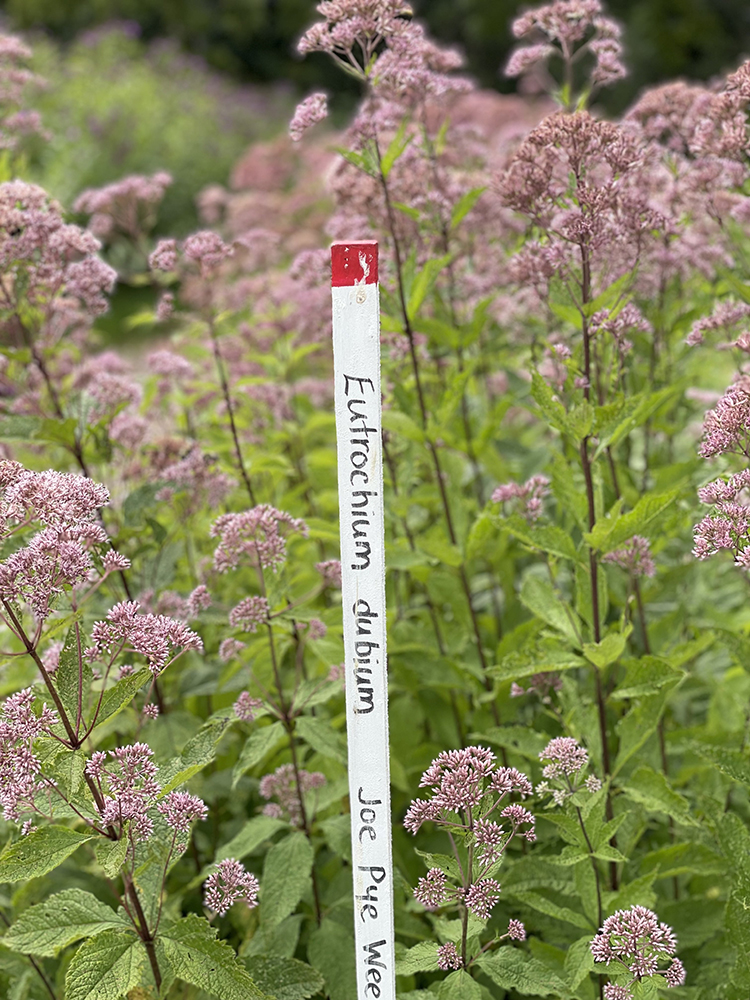

“Rhonda has been a wonderful addition, helping to raise Indigenous issues of concern,” Hayden says. The Partnership has hosted walks led by Nipmuc leaders who discuss Indigenous knowledge and identify plants that are sacred to local Indigenous peoples alongside foresters who bring a more Western perspective to forest management. “It’s been a really interesting dialogue,” she says.

The Partnership’s mission includes land conservation as well as municipal financial sustainability, rural economic development, and education and outreach goals. “The forest economy is an important part of the Partnership’s mission, making sure we have local jobs that are natural resource-based,” says Hayden.

“Rural sustainability will promote conservation,” Crane adds. “If that landscape is seen and recognized as valuable by the community, there is an incentive to conserve it.”

One of the Partnership’s priorities is to reform the Payments in Lieu of Taxes or PILOT program whereby the State reimburses municipalities for lost tax revenue. The current model, which is based on real estate values, favors more densely populated urban communities over rural ones and does not take into consideration the outdoor recreational opportunities and ecosystem services, such as carbon storage, clean water, and clean air, that forests provide.

“The rest of the state benefits from our lack of development. We have an intact forested landscape that provides all sorts of ecosystem services to the entire region, but it’s sort of at our expense because of the lack of development,” Crane says.

RCPs like the Woodlands Partnership bring communities together to address these types of regional issues. For example, the Forest Service’s Forest Legacy Program, which supports forest conservation, is now available to private landowners throughout the region thanks to the Partnership. And participating towns can apply for grants for everything from planting trees and restoring riparian habitat to improving public safety services.

“We’ve had great participation in a state-run grant program specifically aimed at the Partnership region where towns can apply for up to $25,000 for an annual grant for specific local needs,” Hayden says. “Emergency services is one of those concerns regionally, so we’re trying to help and fill gaps.”

The Partnership is also helping towns and forest managers adapt to climate change, including through a collaboration with the Northern Institute of Applied Climate Science, an arm of the Forest Service that helps forest managers develop resilience plans for the long term. The Woodlands Partnership also worked with Mass Audubon and other partners to create The Forest Center.org, a website packed with resources related to climate change, forest stewardship, and planning. It also includes Indigenous perspectives, which are often omitted from such documents.

For Crane, education is the most important benefit of being a member of the Partnership. “There’s a counterintuitive nature to nature,” Crane says. “Getting people to really understand why we’re doing what we’re doing is gonna take a lot of work. As much as it is our responsibility to protect the landscape, it is our responsibility to deal with the problems we have brought to the landscape.”

“I think that’s a strength of regionalism and the RCP concept; land trusts working together to do ever bigger and more impactful things,” Hayden says. “That’s one of the benefits of this Partnership as well. Voices can be amplified when you have your neighboring communities that are facing the same situation speaking up together.”