The federal government is poised to invest billions of dollars into conservation efforts over the next several years through the infrastructure bill and, potentially, the reconciliation bill. Land Justice will be an important factor given the enactment of Justice40, the Biden administration’s Executive Order that requires 40% of the benefits of federal investments on climate and clean energy to go to communities that have been “historically marginalized, underserved, and overburdened by pollution,” attempting to ensure vulnerable communities share in the benefits of that funding. These two developments are driving organizations to dig deeper into the possibilities of advancing land justice in New England and beyond.

Last month at the RCP Network Gathering, New England conservation leaders and practitioners from all backgrounds came together to discuss and collaborate around centering justice and equity in their work. Many of the themes that emerged at the Gathering also surfaced in our recent conversations with New England conservation leaders.

New England’s Nature Gap

Working towards land justice provides an opportunity to address the distribution of benefits from conservation and who has been underserved in the past – a topic explored by Parker McMullen Bushman, keynote speaker at the RCP Gathering and founder of Ecoinclusive Strategies. She explained how “The environmental justice movement was founded because there was not a fair distribution of environmental goods and bads … and the negative impacts of environmental issues were affecting some groups more than others.” Environmental injustice, which is prevalent all around the world, can be seen across the New England region.

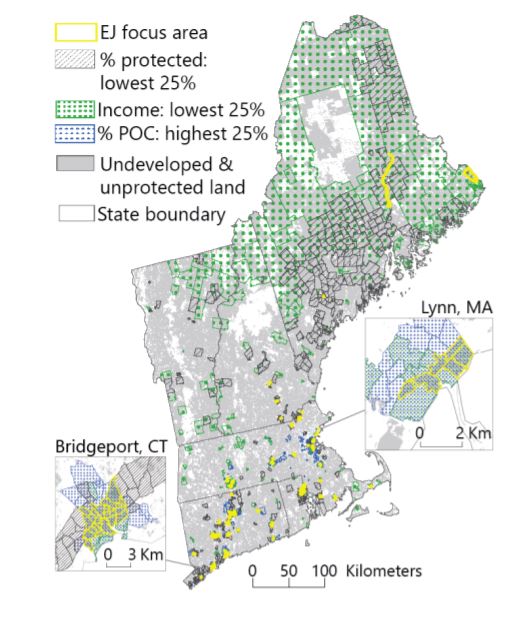

Accompanying a report recently published by Harvard Forest, a map illustrated New England’s environmental injustice areas, where there is both a high degree of social marginalization and a low amount of protected space. The study that underlies that map found that the benefits of conservation have not been made available to these communities. For example, communities in the lowest income quartile have half as much nearby protected land as those in the highest quartile, and communities with the highest proportions of people of color have less than 60% as much protected land. Dr. Neenah Estrella-Luna, co-author of the study and environmental justice scholar and advocate, stressed that “Environmental Justice is a civil rights issue. It is about people having access to the same conditions and the same rights that wealthy and white people have always had access to.” As McMullen Bushman and Estrella-Luna pointed out, environmental justice requires a redistribution of benefits that have traditionally only been made available to a select few.

Opportunities in New Funding

Both the infrastructure and reconciliation bills allocate significant amounts of funding towards conservation, offering an opportunity to address some of the environmental inequities in New England. Kristen Sykes at the Appalachian Mountain Club spoke about how the funding can help address the lack of equitable access to nature in New England: “For a long time, the conversation has been focused on creating new natural spaces. But we’ve found that a lot of folks are surrounded by public lands, but they don’t have the means to access it. Conservation is a really key piece as well, but there’s also the ability to actually get to protected lands.” Sykes highlighted the infrastructure bill’s opportunity to fund more equitable access to nature through a 70% increase in the $1.44 billion per year that goes to the transportation alternatives program, which funds bike lanes, trails, sidewalks, and other active infrastructure. The infrastructure bill will also allocate $200 million a year to the Reconnecting Communities pilot program, which addresses damages inflicted on BIPOC and low-income communities by the highway system, with projects such as highway removals and pedestrian bridges. Complementing this program would be the $3.95 billion Neighborhood Access and Equity Program, proposed in the reconciliation bill, which is still being debated in the senate. If passed, the program would fund a larger range of restorative projects in communities negatively affected by highways.

In alignment with Justice40, significant portions of conservation funding in both bills require that underserved communities be prioritized. This goal, while potentially transformative, currently lacks specific criteria and action steps. Dr. Estrella-Luna emphasized that “One of the biggest challenges around [Justice40] is defining what we mean by benefits. We might need to redefine what we actually mean, and what we have been suggesting is that benefits should always be defined in terms of protecting the most vulnerable people.” Justice40 creates an opportunity to redistribute the benefits of conservation, but how effectively it will accomplish that remains to be seen.

Disparities in Funding Opportunities

Despite the potential funding for underserved communities coming out of the infrastructure and reconciliation bills, some leaders have voiced concern about the funding actually making its way into communities. Amber Arnold, co-founder of the SUSU commUNITY Farm, echoed that concern. “I don’t feel excitement because that money rarely actually reaches projects like ours,” said Arnold. “If that money was actually to go to organizations like mine, Black and Brown organizations, there would be a lot of really powerful work.” Kristen Sykes highlighted many reasons communities may not receive funding: “there are a fair amount of barriers, [including whether] people know about the funding, can apply for it, and have the capacity to apply.” A recent article from the New York Times demonstrated the many obstacles that stand between the most vulnerable communities and infrastructure funding. The article went on to explain that historically, wealthy, white communities with the resources to apply to competitive grants and programs receive the bulk of federal grants. This is because municipalities must be aware of grant programs and have the resources and staff to keep track of them. Another barrier is match– which requires communities to pay a share of the project- which is not possible in towns without available funds. Policy experts are unclear on whether the playing field can be leveled in time for new funding allocations. Awareness of these barriers across the conservation community is a first step in finding ways to overcome them and ensure more equitable distribution of resources.

Redefining Conservation

One theme that emerged at the RCP Gathering was that conservation in the land justice context needs to encompass more than just land protection. Dr. Estrella-Luna highlighted that “Before money becomes available, you need to ask people, what is it that you need to create the conditions so that you can have healthy, safe lives and livelihoods? You need to ask the folks who live in those spaces, go to the community organizations that are serving those communities, and pay them to work with you to identify those solutions.” As Estrella-Luna emphasized, land justice can be accomplished in a number of different ways, and ideas for improving the system should come from communities that are experiencing the injustice. While land conservation efforts for underserved communities are well-intentioned, sometimes solutions are more complex. Ciona Ulbrich, Senior Project Manager at the Maine Coast Heritage Trust and member of the Conservation Community Delegation at First Light, explained “There’s a ‘Land Back’ movement happening where people want to give their land back to Tribes – an important goal. But it’s not as simple as just giving as much land back as possible – that can create problems such as unintended cost burdens. Maybe we can also create opportunities to secure cultural use access rights.”

Land Justice in Action

While the new legislation and funding streams are drawing attention to land justice, many organizations are already working towards making conservation more inclusive and redistributing benefits. Interviewees highlighted how they are tackling land justice in both traditional and alternative ways. “One of the efforts we’re working on is building a toolbox around cultural use,” said Ulbrich. “As examples, we are working with Wabanaki to build cultural access clauses into conservation easements, and with their help we have created a harvest permit that landowners or land trusts can issue to Wabanaki.” Amy Blaymore Paterson of the Connecticut Land Conservation Council pointed to their Regional Land Trust Advancement Initiative Program as another example. She said that “the focus area of the program has evolved to address inclusive conservation” — offering land trusts an opportunity to work with equity trainers to connect with more people, build local partnerships, and better serve their communities. Walker Holmes, Connecticut State Director at the Trust for Public Land, was involved in preserving the farm where Martin Luther King, Jr. worked for two summers in his youth. She says that “there are so many places of great significance to Black history and culture where the stories and sites are in danger of being erased. The terrifying statistic is that only 2% of sites on the National Register of Historic Places focus on the experience of Black Americans. Conservation can help to change that by protecting these places in perpetuity.”

Building Relationships at the Speed of Trust

A common theme echoed by regional leaders for advancing land justice and conservation together is the need to build trust and truly listen to the needs of organizations already doing the work. For conservation organizations and land trusts hoping to work towards a more just and equitable future for New England, there are a few key considerations. Amber Arnold emphasized that “Institutions that are committed to that work need to invest time and energy into building relationships with Black, Brown, and Indigenous people and organizations. They have to trust and allow resources to be distributed in a way that allows people to do the work they want to without having to answer or ask, or have to be in the relationship with these organizations to get the resources they need.” Arnold went on to emphasize that handing over decision making power and decreasing red tape are essential in establishing trust. Ciona Ulbrich recounts her experience in connection building with Wabanaki: “What you do is make mistakes, and keep trying. One of the key things we heard from them was that we kept trying, and we kept coming back. That built respect in our connection-building, because we kept showing up.” Katie Blake, conservationist at Highstead, spoke to the relationship building aspect of land justice. While many are eager to make new relationships, Katie reflected that “it’s urgent, but also must be slow. It’s all at the speed of trust. It can’t be transactional– it has to come from an authentic place.” Organizations already working in land justice, as well as those seeking to do more, agree that success will require coordinated efforts, long-term relationships and deep work. In the words of Parker McMullen Bushman, “When we think about how we solve these issues, we have to look within our organizations and say, how do we get everyone at the table? A lot of times, it takes a fundamental shift. If you aren’t making the changes internally and thinking differently within your organizations then it is harder to make change and sustain change.”

Additional Resources

Author’s Note: While the Infrastructure bill has been signed into law, Build Back Better – the reconciliation bill – remains stalled in the U.S. Senate.