Following months of negotiations, the $2.1 trillion reconciliation bill was passed in the House of Representatives this past Friday, November 19th. The reconciliation bill will now move to the Senate for a vote, where some budget changes are expected. If passed in the Senate, the bill will ultimately be sent to Biden’s desk to be signed into law.

With $550 billion towards climate change mitigation, the bill sets a historic amount of funding aside for natural climate solutions. Encouragingly, the funding for natural climate solutions and conservation have stayed strong even as the bill was trimmed down from around $3 trillion during negotiations. The reconciliation bill invests over $40 billion in forestry, including $3.75 billion for State and Private Forestry programs such as the Forest Legacy Program, and $28 billion for farm and forest conservation. For a more in-depth look at the reconciliation bill’s allocations towards conservation, refer to the first and second articles in this series.

The reconciliation bill is closely linked to the infrastructure bill that was passed earlier in the month, and together they are a powerful force and set out some of the most significant climate change goals ever set by the U.S.

With a plethora of new federal funding likely coming to conservation across the U.S, we sought insights from regional conservation leaders on the important next steps for the conservation community in New England. The consensus is that now is the time to pull together to strategize and prioritize around the new funding to speed implementation of critical projects.

Regional Readiness through Collaboration

While funding pathways and timelines are not yet clear, it’s time for regional conservation partners to start thinking about how they can best utilize new funding. Heather Clish, the director of conservation and recreation policy for the Appalachian Mountain Club emphasized that “We should identify the really good projects that the community wants to pursue – the opportunities that are ripe for collaboration, and now is the time to shift very rapidly to getting specific thoughts in mind.”

Even more regional collaboration, as practiced by dozens of existing Regional Conservation Partnerships (RCPs), was also encouraged by conservation leaders. Eric Wasburn, president of Windward Strategies, agreed that “New England as a region can pull together a multi-state, climate resiliency and land connectivity plan; and through the appropriations process, steer as much money towards New England as possible.” When it comes to regional readiness and collaboration, RCPs put New England in a great position to prepare for this influx of funding.

One illustration of regional readiness was offered by Markelle Smith, a member of the Friends of the Conte RCP and landscape partnership manager for The Nature Conservancy in Massachusetts. Member organizations of the Friends of Conte contributed to a ‘Look Book’ of potential projects. Markelle explained, “We don’t know the specifics, but it sounds like the funding will be funneled through Partners of Fish and Wildlife and be dispersed in that way, and so we wanted to showcase the restoration and stewardship projects that Conte and the Friends have ready to go. This is an attempt to get ahead of the infrastructure bill and make sure that legislators and our partners at US Fish and Wildlife Service know that we’ve got projects ready for implementation.”

Prioritizing Climate and Closing the Nature Gap

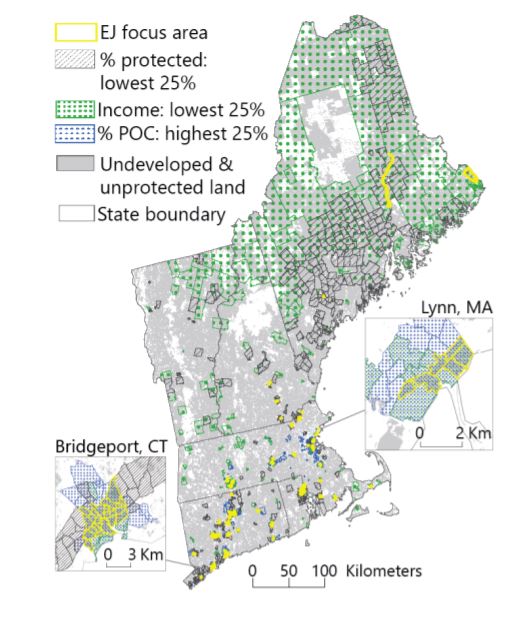

While the new levels of funding will come through many familiar programs, some of the new details and program rules will incentivize or even require that projects address elements of climate mitigation and environmental justice. “The environmental justice criteria provide an incentive for organizations to find a way to link urban, suburban and rural projects that specifically address the needs of disadvantaged communities,” says Tara Whalen, conservationist at Highstead.

Jad Daley, president of American Forests, added that funding will also require a new climate-specific way of thinking of conservation projects. “To be successful, projects will need to integrate a new approach: the climate criteria are written into a lot of these; it’s not just more Forest Legacy money, but seeks to advance forest conservation that’s tied to climate change criteria in a very explicit way.” The Section by Section Rules Committee Print of Build Back Better backs up Daley’s assertion by showing that grants through the Forest Legacy Program will prioritize projects that “offer carbon sequestration benefits, or contribute to the resilience of community infrastructure, local economies, or natural systems, or to underserved populations.” These priorities were reiterated on many other existing funding program guidelines and set a new standard for how certain projects will be evaluated.

To address environmental justice, many of these funding allocations call for prioritizing underserved communities, and federal entities will have to decide how that actually gets done. Heather Clish noted: “[New England has] globally significant forests, so we should be a hotspot for this kind of investment. But we also have a nature gap, where white communities have better access than communities of color.” Environmental justice provisions for conservation funding support Justice 40, the Biden administration’s initiative that calls for 40 percent of the benefits from investments in climate and clean energy to be delivered to disadvantaged communities, and this includes the funding in the infrastructure and reconciliation bills.

Matching Funds

Another key aspect of regional strategy is being able to gather required matching funds from private and non-federal public sources. While matching has been waived for certain programs, most relevant programs for our conservation partners would require some degree of match, similar to existing programs. Regional conservationists echoed a concern to meet match requirements and encouraged an immediate consideration of how matches are going to be made. Shelby Semmes, vice president for New England at the Trust for Public Land explained that: “ [If] states or municipalities don’t have ways to match that money, you’re going to lose out on it. To the degree that the conservation community can put pressure on traditional state funding sources or local funding sources, particularly with an eye toward equitable distribution of that money, that might be an important message.” By knowing where limitations and opportunities on matches stand, conservation projects can be best positioned to take advantage of funds effectively. For example, leaders could revisit ideas like the “pooled match inventory” approach that the RCP Network used to match NRCS Regional Conservation Partnership Program funds in recent years.

Walker Holmes, Trust for Public Land’s state director for Connecticut commented, “Now is the time for us to think creatively about what we might do, what conservation finance strategies have we not yet brought to bear? They would need to be very equity-forward, and municipalities and the state are going to have to set their priorities based on what people believe to be the most beneficial for the communities. We have to make the case for why these things proceed to generate jobs, produce revenue, benefit the community, and [advance] health and climate equity.” Recent Highstead Case Studies highlight the link between land conservation and economic development in New England.

Collaboration Could Ease Challenges to Using the New Funding

Regional conservation leaders had multiple ideas of what might be the best way to meet matching challenges. “Linking funding for conservation that simultaneously provides clean water and climate benefits is a win for the environment and communities,“ said Spencer Meyer, senior conservationist at Highstead. One way to do that is through a lesser-known potential matching strategy using the Clean Water and Drinking Water State Revolving Funds. State revolving funds (SRFs), which target water infrastructure, are eligible for conservation projects that provide an improvement in water quality or systems. SRFs will see a major increase of funding with the implementation of the infrastructure bill. There is growing interest in using SRFs to finance green infrastructure, and conservation groups are beginning to innovate to use them. Terisa Thomas, now with Quantified Ventures, crafted the Vermont legislation that expanded the eligibility of the funds, and she sees possibilities for conservation projects and hopes to “Empower these groups to understand the untapped incredible power of the SRF.” The Trust for Public Land has utilized SRFs for land conservation in Vermont, and Brendan Shane, climate director at the Trust, remarked “Different conversations are being had where people have tapped into some of those clean water funds, but they’re going to see a major increase, and there’s ability to do water projects that also have conservation benefits…I think there’s opportunities there.” Portland Water District in Maine has also begun using SRFs to finance forest conservation projects. SRFs are one tool conservationists should increasingly look to for funding urgent conservation projects.

Tim Abbott of the Housatonic Valley Association, who has helped aggregate stakeholders and projects to meet federal match requirements, highlighted that there is significant opportunity for these partnerships in the region, encouraging states to prioritize them, and commenting that conservation funding “Can be more efficient and more effective if we engage in public-private partnerships.” Abbott stressed that New England, with its RCP Network, is especially well-positioned to take advantage of public and private partnerships.

Some leaders pointed to potential challenges in the effort to distribute funds effectively. Being cognizant of these barriers early on in the funding process is essential, as regional players have the opportunity to get creative on problem solving. Tim Abbott saw a need for additional administrative capacity at the state agency level. He highlighted that “the other place we’ve got to be creative, I mean massively creative, is in giving state agencies more money for more staff to be project managers. There are bottlenecks everywhere.” He observed that projects would be initiated but end up sitting around for a long time because there was not enough staff capacity to effectively manage project timelines and objectives.

Another barrier to funding was emphasized by Brendan Shane at the Trust for Public Land. Shane had concerns about workforce and supply chain volumes with a massive influx of funding. “There’s a real question for urban and community forestry funding, ” adds Shane. “It would be an immediate five-times increase, so there are a bunch of folks looking at that question of how to build a pipeline, across the supply chain for trees and greening and then the workforce for planting and maintenance and careers in forestry and related work.” Supply chains and workforce challenges, which are playing out at the national level right now, are also a necessary consideration for next steps in conservation funding.

What’s Next?

The massive influx of funding from the infrastructure and reconciliation bills has the potential to propel conservation projects in the New England region. Considering all the potential barriers and opportunities surrounding this new legislation is crucial to our region’s next steps in utilizing the expected conservation funding. Throughout our interviews, the topic of equity consistently came up as a priority for funding allocation.

The next article in the series will cover updates on the reconciliation bill as well as Justice 40 and equity in relation to new funding. When asked about justice and its ties to this funding, Tim Abbott stressed that “Environmental justice, equity, all of those questions are immediate, and particularly because the kinds of infrastructure projects that might get funded need to be different than the ones in the past that have adversely impacted many of those communities.”

In the meantime, we look forward to collaborating with many of our New England partners to prepare for the new conservation funding emerging from Congress.

Note from the Editor: Highstead Conservation intern Jackie Rigley will complete her semester-long assignment in mid-December. The series will continue under the leadership and authorship of Highstead’s Tara Whalen, Conservationist and Spencer Meyer, Senior Conservationist.