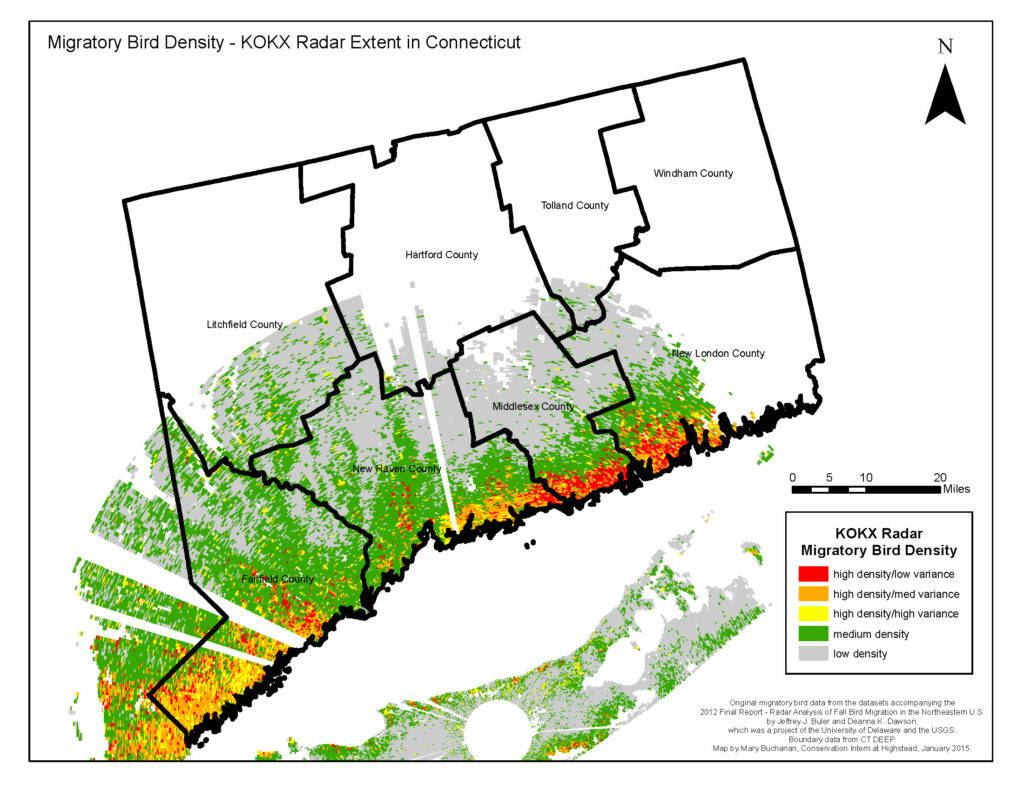

The Highstead landscape awakens on spring and summer mornings with a special beauty. Dew evaporates from the hilltop grassland meadow, leaves in the oak and red maple forests unfurl, and various birds break into song. These avian inhabitants choose the Highstead landscape where a mixture of habitat is available for their year-round, migratory, breeding, or nonbreeding needs. Highstead bird communities consist of species with wide geographical ranges, different ecosystem niches, and particular life cycle needs.

Whether busy flying overhead or ground feeding for insects and worms, these different birds are key players in the everyday ecological processes unfolding over seasons. Ruby-throated hummingbirds assist with essential pollination and blue jays with seed dispersal of oak trees, while red-bellied woodpeckers and other birds feed on “pests” and insects, keeping populations under control. Some species, like the barred owl, scavenge carcasses and control the population of rodents and small mammals. Further, birds are reliable bioindicators of environmental health or decline. For example, the American woodcock is sensitive to pesticide and heavy metal accumulation.

Get to know 10 species of birds at Highstead that reflect different habitat niches, and particular life cycle needs. Perhaps you will find them in your neck of the woods or have an opportunity to see them among the meadows, forests, and wetlands at one of Highstead’s future in-person guided walks.

Birds of Highstead

1. Bobolink (Dolichonyx oryzivorus)

Bobolink are a charismatic grassland specialist with a unique, bubbly song and color patterns. As one of our longest-distance migrants, this songbird arrives in Connecticut in early May after flying about 6,000 miles from the grasslands of central South America.

Since they prefer tall grasslands, uncut pastures, prairies, and overgrown fields, New England populations historically grew after European colonization brought large-scale deforestation and agricultural expansion.

2. Blue-winged Warbler (Vermivora cyanoptera)

Where and when can you find the Blue-winged Warbler around Highstead and the Eastern region? These songbirds sing their buzzy insect-like song seemingly without end in the early part of their breeding season (May-June) throughout Highstead’s maple-ash wood canopy gaps. They specialize in shrubland habitat or forest openings where regenerating vegetation or a dense shrub layer occurs. On these shrubs, bright yellow-green male warblers sing for a mate and may even harvest insects from leaves by dangling upside down.

Due to their specific habitat needs, Blue-winged Warbler populations are generally in decline following decades of landscape changes and forest maturation following agricultural abandonment; however, the IUCN Red List categorizes Blue-winged Warblers as a species of Least Concern.

3. Pileated Woodpecker (Dryocopus pileatus)

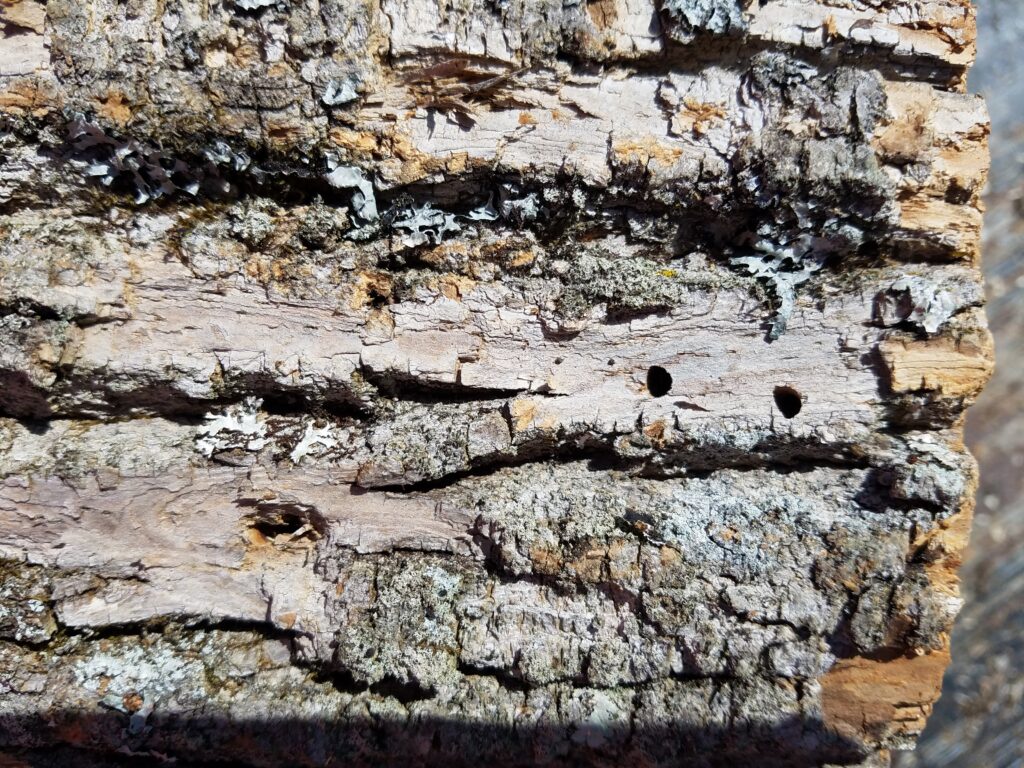

This large (crow-sized) Highstead forest-dweller forages for insects like carpenter ants and the larvae of wood-boring beetles, like the invasive emerald ash borer. Their efforts leave rectangular holes in live, dead, or dying trees and logs—you might find deep cavities in rotten wood where woodpeckers nest, roost, and search for food. Look high and low as Pileated Woodpeckers fly and forage in the upper forest canopy and at the base of large trees in mature forests.

Male birds will drum into trees throughout the winter season in their efforts to set and defend their territory. Both male and female birds partake in drumming as part of their courtship rituals in the spring. They may also drum in response to intrusion upon their nests.

Due to their habitat requirements, Pileated Woodpeckers need large alive and dead standing and fallen trees for both the insects they provide and as containers for their large nest cavities. Their numbers are increasing as forests age and their status is evaluated as a species of Least Concern on the IUCN Red List.

4. Veery (Catharus fuscescens)

Ever heard a Veery “veer”? In late spring and throughout the summer, Veery will sing a spiraling song around dawn and dusk, particularly in forested wetlands, like the Red Maple Swamp at Highstead. After an impressive migration of continuous flapping on their strong and efficient wings—they have been tracked to travel up to 160 miles/285 kilometers in one night’s flight. These thrushes will spend the warmer seasons among their breeding grounds in New England, across the upper Midwest, and into Canada. They breed in wet areas, in interior deciduous forests, near streams and swamps, and where dense understory offers protection for their nests.

Unfortunately, Veery populations are decreasing. According to the North American Breeding Bird Survey, Veery declined over their range by 42% between 1966 and 2014. South American forest transition to agricultural land-use practices and fragmented forest breeding habitat in the northern hemisphere may be to blame. However, Veery is a species of Least Concern on the IUCN Red List.

5. Eastern Kingbird (Tyrannus tyrannus)

The Eastern Kingbird patrols the skies over the Highstead Pond for flying insects that make up most of its spring and summer diet. Once the seasons pass, the aggressive flycatcher will winter in the forests of South America and subsist on fresh fruit. While at the pond, the territorial kingbird will work to chase larger birds like crows, hawks, and herons away.

Its scientific name, Tyrannus tyrannus denotes “tyrant” or “king,” but its title is not the only characteristic that demands attention. Notice the golden cap on its head? Other kingbirds may have orange or red crowns, but this distinctive feature may remain concealed until a potential predator arrives, when a kingbird may raise its crown before diving at the intruder in an attempt to thwart them. Listen for their song, which can be described as a current of electricity running through a wire.

Data from the North American Breeding Bird Survey (BBS) indicate that 47% of Eastern Kingbird decreased between 1966 and 2017, an era of habitat loss and degradation from human development as well as forest succession, increased pesticide and insecticide use, and reduced prey abundance. Eastern Kingbird is a species of Least Concern on the IUCN Red List.

6. Eastern Phoebe (Sayornis phoebe)

“FEE! BEE!” Eastern Phoebes are among the first migratory birds to arrive at Highstead, and the last to leave their New England breeding grounds for their winter homes as far as Mexico. In New England, Phoebes favor brushy habitats like woodland and pond edges, where they hunt for flying insects.

These flycatchers will make themselves at home among rock ledges and human-made structures like bridges and eaves suitable for their nesting (including those on the Highstead barn). One way to tell if you’re looking at a Phoebe is to notice if their tails bob up and down when perched. Phoebes are usually sighted near the Highstead Barn.

7. Eastern Bluebird (Sialia sialis)

The scattered trees, meadows, and partially open habitat throughout the Highstead landscape appeal to the Eastern Bluebird. These small thrushes are fairly common in our region. Despite urbanization, pesticide application, and competition from other cavity-nesters like the non-native European starling and house sparrow, bluebird numbers are increasing. Human-made nest boxes have become a suitable aid for Eastern Bluebirds when available cavities are harder to find.

8. Scarlet Tanager (Piranga olivacea)

What was that red flash? A trick of the eye? A cardinal? No it’s even brighter red! Once you get a closer look— or hear the raspy, rambly “chick-burr” beckon you through Highstead’s mature oak forest, you’ll find a Scarlet Tanager.

The male birds are bright red in body, contrasting against the green and browns of a temperate woodland habitat, with black wings and tail. They are denizens of the canopy of tall and undisturbed forest tracts, and breeding pairs will nest high in the trees among pine-oak, oak-hickory, beech, hemlock-hardwood, and even boreal forest stands as far north as Canada. Females and immature males blend more among their surroundings in olive and yellow feathers and darker tails and wings. After the breeding season, adult male plumage will molt to a yellow-olive color while retaining their black tails and wings.

9. Wood Thrush (Hylocichla mustelina)

Come May, Wood Thrush arrive to breed in Connecticut and deciduous New England Forests from wintering in forests as far south as Panama to southern Mexico. While they are generally an interior forest bird, you may also see or hear their “ee-o-lay” song in residential areas or among forests edge. Understory species like spicebush and blueberry are some of the Wood Thrush’s favorite regional plant foods, and small invertebrates and even salamanders are some of their prey.

The species’ status improved in the 2020 IUCN Red List update to Least Concern after seven years of being labeled ‘Near Threatened’. This may be due to improved habitat stewardship and data collection, but Wood Thrush remains a declining species in our region. The North American Breeding Bird Survey details a total population decline of almost 50% between 1966-2019.

10. Barred Owl (Strix varia)

Highstead’s most common resident owl is the Barred Owl. You’ll often hear their characteristic hoot (“who cooks for you?”) day or night in the mixed and mature oak forest and wooded wetlands at Highstead. This species does well in deep, unfragmented woods that support optimal habitat like old trees for cavity nesting and small prey animals like invertebrates, reptiles, amphibians, chipmunks, voles, mice, and other birds.

Beyond its origins in the eastern United States, Barred Owl ranges extend into Canada and through the South and Midwest, bypassing most western states except for Idaho, Montana, and the Pacific Northwest. Overall, populations are increasing, but the species’ habitat requirements leave them sensitive to tree harvest or severe forest fire activity. Their IUCN Red List status is Least Concern.